In The Internal Crusade, Chinese-born photographer Zexuan Zeng traces the long shadow of the Long March — not as an episode in history, but as an enduring metaphor shaping the collective imagination of a nation.

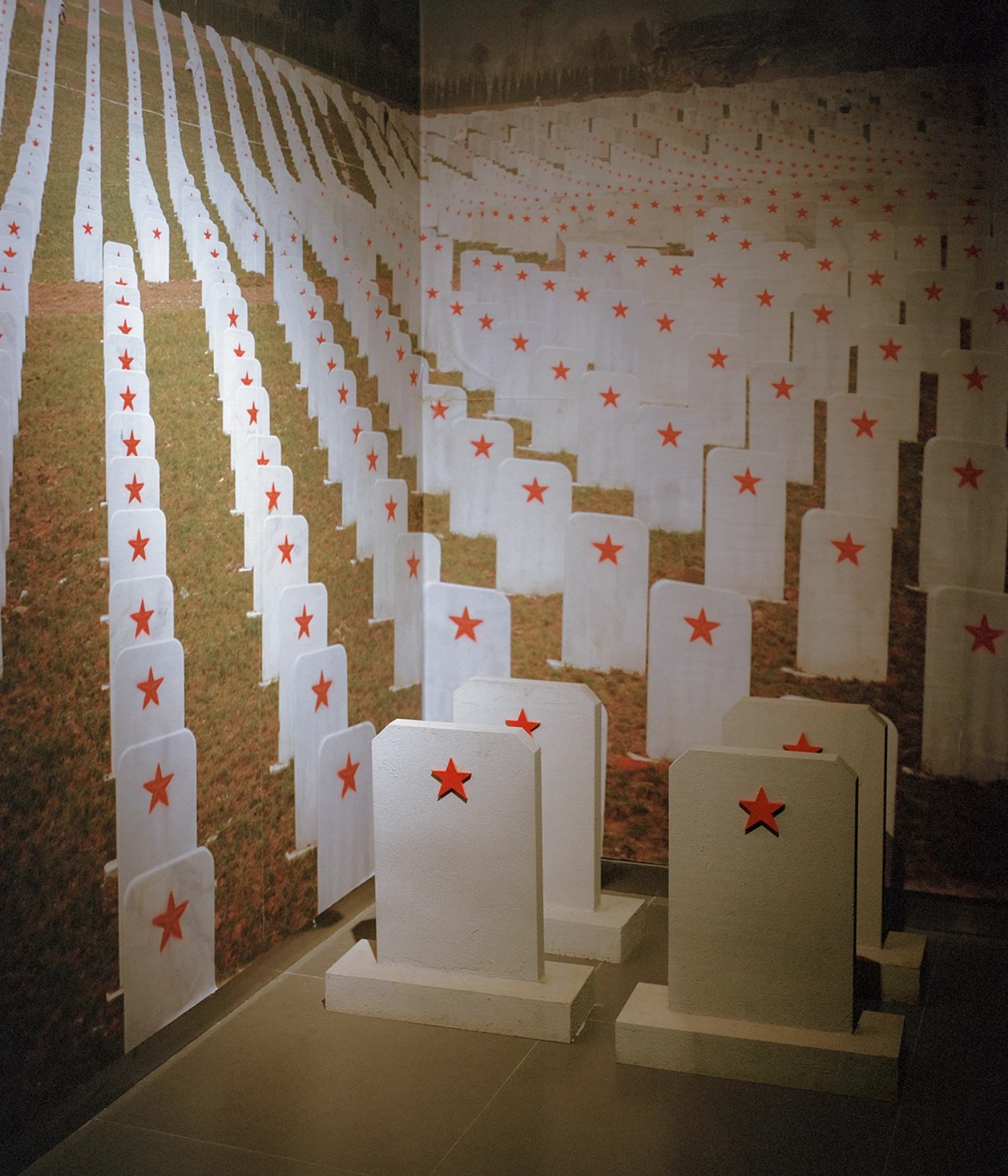

The project is both a journey and a reckoning, one that threads through the landscapes, monuments, and memories lining the historic route of the Communist Party’s Red Army. Zeng’s lens turns this monumental narrative inside out, revealing what happens when ideology settles into the texture of ordinary life.

Zeng was born in 1997 in Ganzhou, Jiangxi province, the place where the Long March began. Growing up surrounded by patriotic murals and slogans, he learned early how collective memory could inhabit public space. “In my hometown, every street corner carried traces of the Long March,” he recalls. “The stories, the signs, the symbols—they were part of the air.” After studying Visual Communication at Shanghai Normal University, Zeng worked as a freelance artist and designer before moving to Germany to study at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne. His practice now moves fluidly between photography, video, and installation, drawn to the uncertain boundaries between documentary and fiction, truth and myth, personal and collective experience.

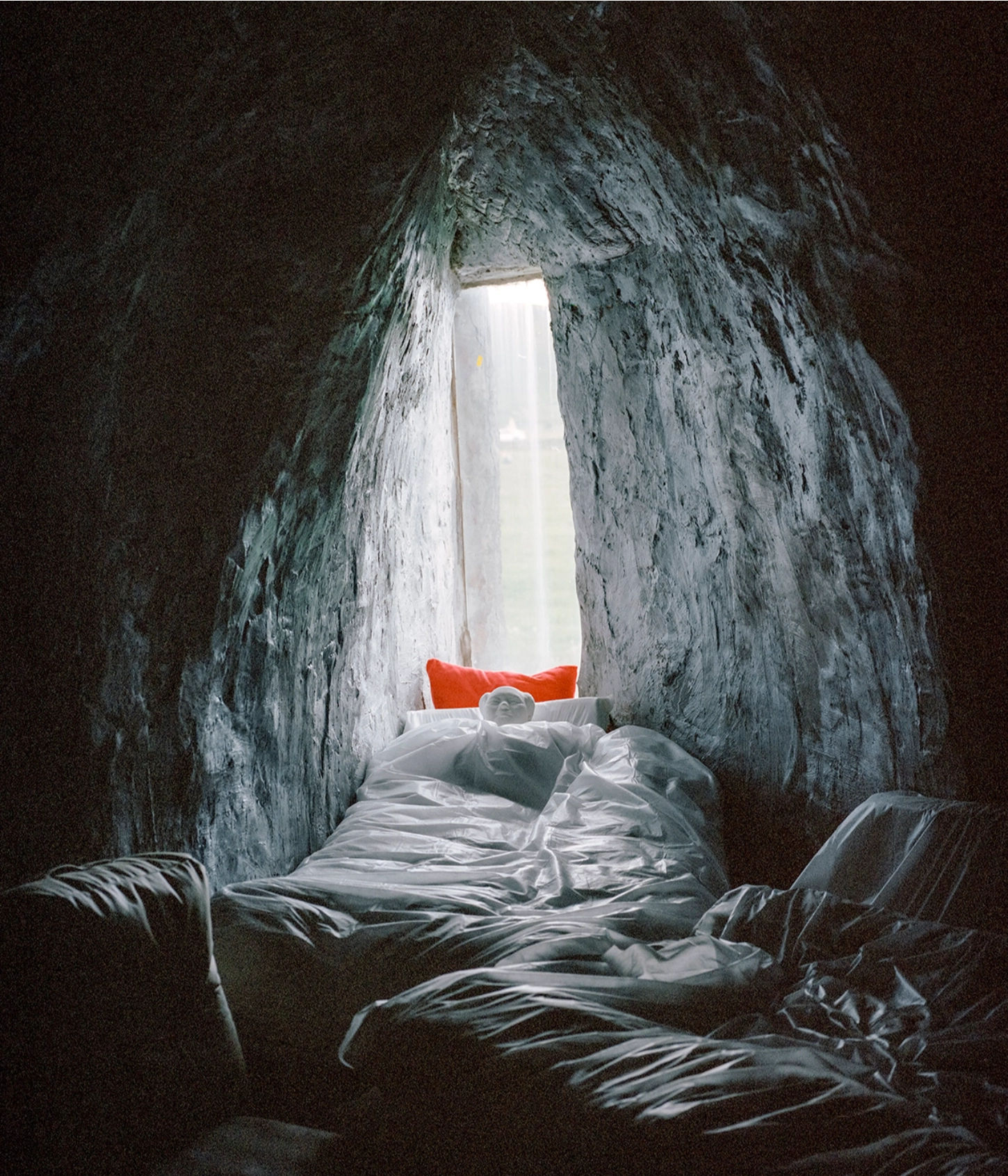

In the summer of 2024, Zeng spent two months retracing the path of the Long March. What he found was neither the triumphal march of textbooks nor the romanticized saga of propaganda films. Instead, he encountered the faded remnants of a myth still alive in the landscape: a cracked monument on a dusty roadside, a shop sign painted in revolutionary red, a school mural slowly peeling in the sun. The photographs are quiet and ambiguous, oscillating between the factual and the symbolic. They are less about the Long March itself than about how its meaning endures—and mutates—through repetition and ritual.

“I began to realize that it evolved into a political tool for transforming individual suffering into a necessary sacrifice required by the collectives,” Zeng writes. “The meaning embedded is that all suffering is a journey, and all journeys must lead to success.” His images, with their subdued light and restrained compositions, resist this inevitability. They linger instead on uncertainty, on what lies between devotion and disillusionment. There is a sense of melancholy running through the work, a recognition that the grand narrative of heroism has blurred into the everyday struggle to make sense of history.

The internal crusade of the title refers not only to the artist’s physical journey but to a psychological one. It is the process of unlearning a story told since childhood, of facing how memory and ideology intertwine. The landscapes Zeng photographs seem to hold both reverence and fatigue; the faces he encounters carry traces of faith and doubt. Through these images, the Long March becomes a mirror for a broader human condition—the desire to find purpose in hardship, and the danger of mistaking endurance for meaning.