O'flower by plainoddity in Seoul strips floristry of its sweetness—a space where flowers become specimens and customers become researchers.

The conventional flower shop trades in soft associations: romance, sympathy, celebration, apology. Petals and stems occupy vases on pedestals, arranged to trigger emotional purchase. For O'flower's second location in Seoul's Dongtan New Town—an area dense with IT companies and young professionals—the design studio plainoddity proposed something deliberately colder: what if flowers were approached with the same clinical curiosity as chemical compounds?

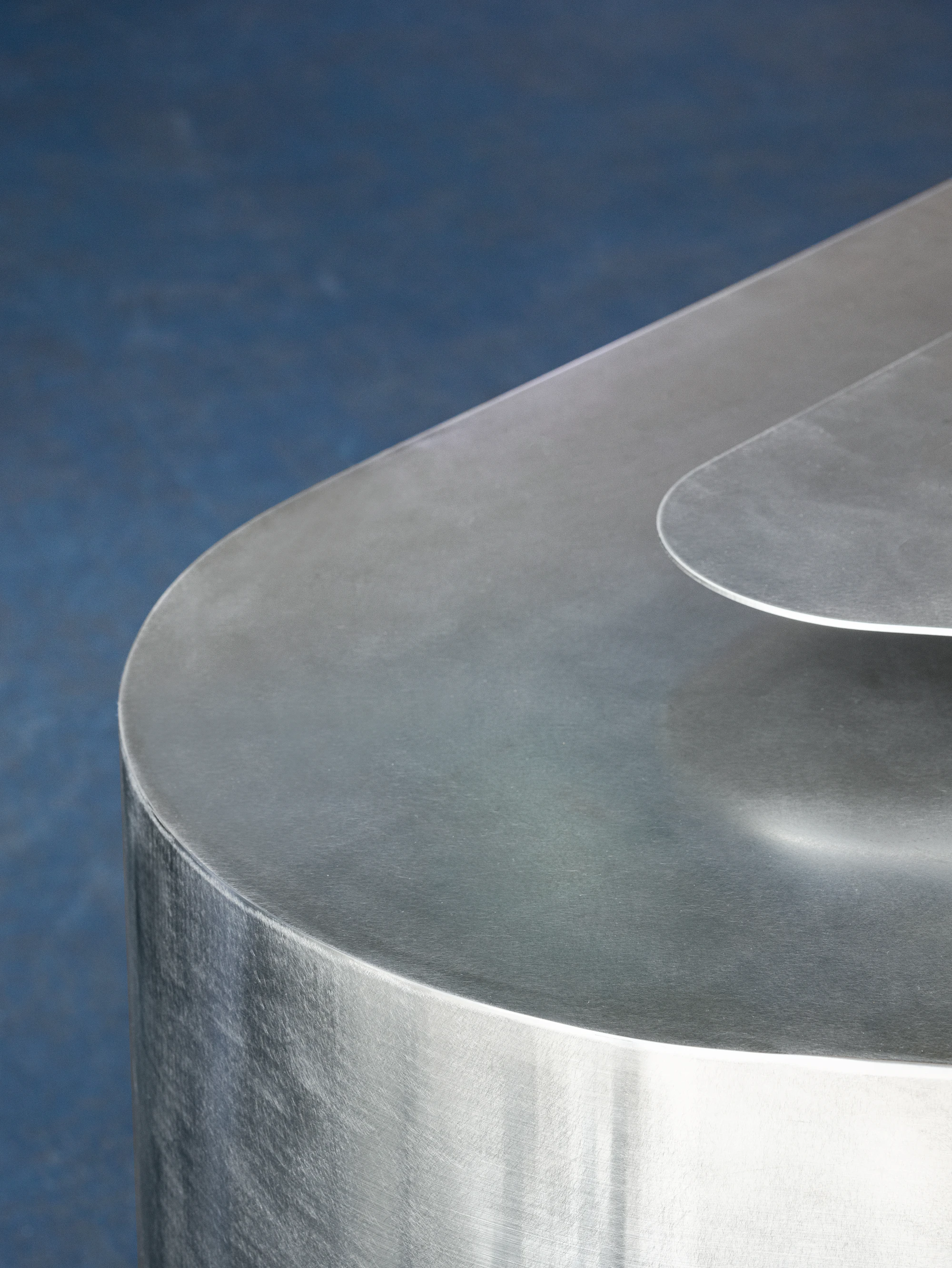

The resulting space resembles a research facility more than a retail environment. Stainless steel fixtures—worktables, display cases, storage units—populate the room with laboratory precision. Walls and ceiling wear a particular shade of sky blue that suggests neither warmth nor coolness but rather a kind of atmospheric neutrality. The flowers themselves, isolated in clear vessels and backlit for examination, become objects of study rather than sentiment.

The arrangement is deliberately disorienting. Display cabinets double as spatial partitions, creating a maze-like sequence through which customers navigate toward the inner workshop. Here, the laboratory metaphor deepens: visitors can assemble their own bouquets through a DIY process, handling stems and foliage with something approaching scientific methodology. Classes and workshops turn casual customers into amateur researchers.

Plainoddity's intervention extends O'flower's brand strategy into three dimensions. The company has built its identity on reducing the perceived distance between customers and flowers—demystifying what can feel like an intimidating purchase. By framing the shop as experimental space rather than curated gallery, the design invites active participation over passive consumption.

The chrome and blue palette also serves practical ends. Flowers read more vividly against cool backgrounds; metallic surfaces clean easily and resist the moisture that accompanies living material. But the conceptual proposition remains primary: that beauty might be better understood through inquiry than through acquisition, that the most interesting relationship with flowers begins when we stop treating them as mere decoration.