In Galeria Arsenal’s industrial shell, Katalin Kortmann Járay and Karina Mendreczky compose a porous landscape where vegetal steel and embryonic figures coexist, not as symbols, but as a speculative ecology.

Beauty was a Savage Garden feels less like an exhibition and more like an excavated mythology, unearthed from a marsh that never quite belonged to human time. Their point of departure is the legend of Hany Istók, the amphibious child found in the Hanság marshes in 1749—a figure suspended between taxonomy and fable. Here, he becomes not a protagonist but a gravitational force that pulls the installation toward a realm where survival mutates into ornament, and ornament mutates into prophecy.

At the center, a vertical sculptural crest rises like a heraldic device for a lost species. Its fetal forms, piscine bodies, and curling vegetal limbs feel neither archaic nor futuristic. Instead, they occupy a liminal register—something akin to a taxonomy drafted by water rather than reason. The artists assemble this hybrid organism with an almost medieval sense of symmetry, yet its materials betray a contemporary precarity: rusted rods, matte clay skins, and fragile protuberances that appear both organic and manufactured. This tension—between sediment and artifact, between bodily memory and botanical speculation—animates the entire installation.

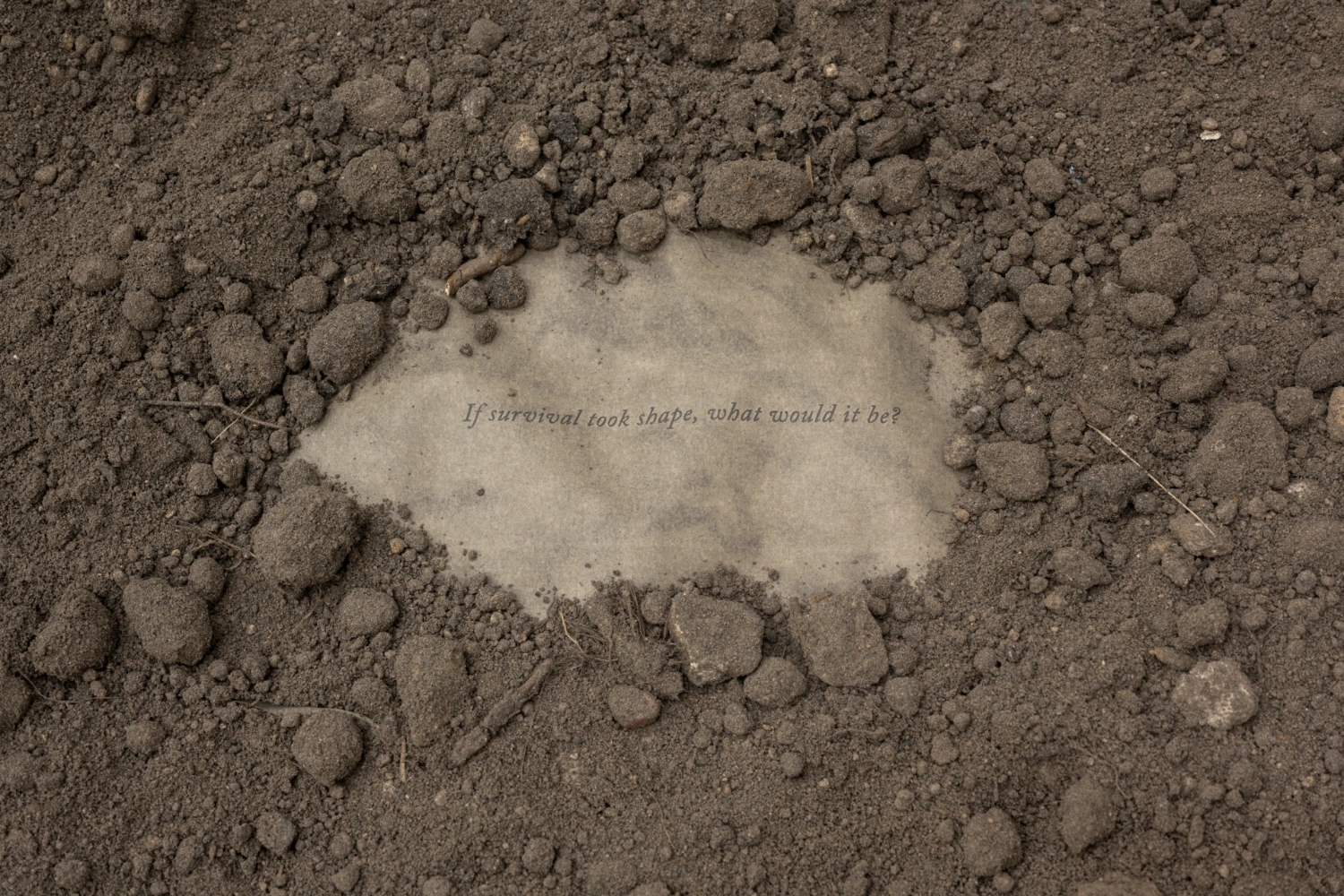

The soil that spreads across the gallery floor reads as both stage and wound. Out of it emerge metal flora with serrated leaves and spiked blossoms, as if the plants themselves have adapted to a harsher atmospheric regime. These are not restorations of nature; they are evolutions born from pressure, mirroring the climate anxieties the artists explicitly acknowledge. Within this landscape, language appears sparingly, embedded like a soft whisper in the dirt: If survival took shape, what would it be? It is less a prompt than a geological imprint of doubt, a recognition that survival today is not a static noun but a continuous reshaping.

Mendreczky and Kortmann Járay resist the dichotomy between the civilized and the barbaric by rendering both categories irrelevant. In their world, the so-called wild is not a regression but a recalibration, a return to sensing rather than dominating. Even the clay ear—a quiet, uncanny relief with moth-like creatures resting on its ridges—functions as a reminder that listening may be the only viable form of adaptation left. The installation proposes an ethics of permeability: bodies that take on plant attributes, plants that behave like sentient witnesses, and mythological children who reclaim their origin by refusing to be domesticated.

Beauty was a Savage Garden stages an ecosystem where tenderness and fierceness become indistinguishable. The marsh of Hany Istók is reimagined as a threshold world, one in which identity is not lost but shed like a skin, allowing for new, necessary mutations. This speculative garden is not utopian; it is resolutely post-human, attuned to the complexities of a planet reorganizing itself in real time. In that sense, the exhibition becomes a quiet manifesto for rewilding the imagination.